“Collieries where a thousand men had laboured for a hundred years became silent fields around a concrete shaft-cap.” Neal Ascherson, Stone Voices

I’ve lived in Midlothian for 13 years. The visual signifiers of the county’s industrial heritage are largely gone: demolished or overgrown. It wasn’t just coal: shorelines on either bank of the Forth once boasted vibrant salt industries, and paper mills once dotted the banks of the Esk. But from the nineteenth century until the late twentieth, coal was the dominant industry in the area around Dalkeith.

The pithead winding gears are all but gone – Newtongrange’s Mining Museum is the outstanding exception to the rule – and the sites of many old collieries are now light industrial estates, or housing developments, or countryside: hillocks more or less natural to the casual glance but which lack the mature woodland you’d expect of their landforms.

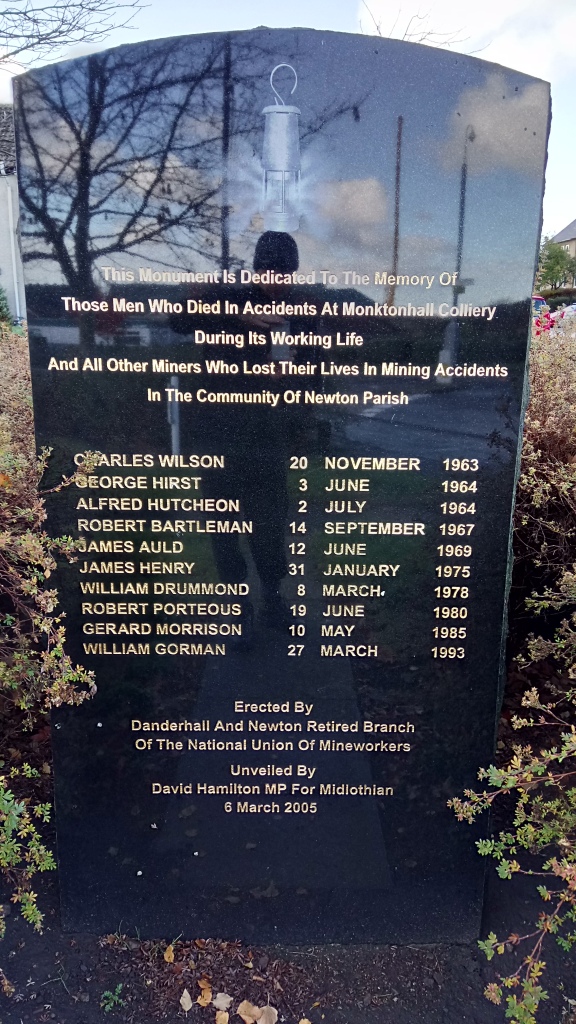

I took a walk one autumn morning to the site of two former collieries: the neighbouring pits of Woolmet and Monktonhall. Starting in the village of Danderhall, at the edge of the village I find a Miner’s Memorial Garden.

Before I start, and with no sign of industrial activity other than the frantic house-building that heralds the growth of Shawfair new town (of which more later), I’m given this cautionary welcome. People died here; on average, one every three years. Spookily, the last man to die shares my Dad’s name. He was killed by a roof fall, the only miner to die in the brief period that Monktonhall was run by a miners’ co-operative.

I start along the path between the new development and the site of the curiously-named Woolmet (the name means “hermit’s retreat” or “place of the cave”). The pit itself closed in 1966 and was latterly a training centre, appearing on OS maps as late as 1988. But all that’s gone, replaced by a gently rounded hill formed of the pit spoil. The slope nearest Danderhall bears the scars you’d expect of such wasteland: beyond the rusting goalposts, three burned out motorcycle chassis sink into the black soil amid energy drink cans which, unlike the bikes, do not rust. There is a grey petrochemical film on the puddles.

One side of the hill feels like a down, hollowed out by rabbit warrens and bare of trees:

But the eastern slope is thick with birches – those early colonisers – and orderly rows of planted firs. In the distance, the Millerhill incinerator nears completion. In the low November sun its bright geometries form a stark but pleasing contrast to the russets and browns of autumn leaves.

At the summit – such as it is – of Woolmet hill stands a plinth whose plaque is missing. This photo shows what it used to look like (I presume the trolley is now part of the memorial garden in Danderhall). Sodden firework casings suggest the place has some local significance, even if just as a handy vantage point. A post-industrial beacon hill.

Descending through the trees, I follow the path to the A6106. The underlying red stone shows through black s(p)oil.

The sign welcoming the visitor from the main road, with its reference to Lothian Regional Council, dates it to the early 90s at the latest. Woolmet was closed (management claimed it was “exhausted” and “uneconomic”; the workers were unconvinced) when the neighbouring Monktonhall complex opened, and the workforce transferred to the new colliery.

Later I discover that though I’d walked over the site of the old bing, the colliery buildings themselves had stood further north, just past the cul-de-sac of Moorfield Cottages. Amazingly, singer and activist Paul Robeson visited Woolmet in 1949. He’d been invited to perform a miners’ benefit concert at the Usher Hall by the NUM.

I cross the road to the turn-off for Woolmet’s usurping neighbour. Monktonhall was a super-pit, like Bilston Glen in Loanhead: the two were jewels in Scottish coal mining’s crown. Three-quarters of the output from Monktonhall went straight onto freight trains bound for the nearby – and recently demolished – Cockenzie power station. These trains travelled with the speed of an inter-city, and such was their frequency that the service was nicknamed the “merry-go-round”. Cockenzie’s relentless burning of coal – unthinkable today – fed these power lines.

I cross the road to the turn-off for Woolmet’s usurping neighbour. Monktonhall was a super-pit, like Bilston Glen in Loanhead: the two were jewels in Scottish coal mining’s crown. Three-quarters of the output from Monktonhall went straight onto freight trains bound for the nearby – and recently demolished – Cockenzie power station. These trains travelled with the speed of an inter-city, and such was their frequency that the service was nicknamed the “merry-go-round”. Cockenzie’s relentless burning of coal – unthinkable today – fed these power lines.

The road to the site of Monktonhall is also that to Shawfair railway station. Built as part of the Waverley line’s re-opening, it’s a station patiently awaiting the growth of the town around it. Ultimately, Shawfair will fill the gaps between the existing villages of Danderhall, Newton and Millerhill. Just now it’s a station, a park and ride, a private hospital, the headquarters of the SQA and – the sole reference to a once mighty industry – a pub called The Old Colliery.

Monktonhall means “the hall of the farm of the monks” in reference to the once-powerful Newbattle Abbey which owned much of the land hereabouts from its founding by David I in 1140 until the Reformation. The first record of coal-mining was by those monks; fittingly, this space pretty much marks the end of the industry, too. Also down this road is Harelaw, whose name means “hill of the hare”, but I see no hares today.

Kerbstones and car-park markings remain but the twin winding towers, designed by Egon Riss*, are long gone:

Monktonhall was itself built on a spot previously occupied by a row of miner’s cottages (Adam’s Row) built to house those who worked in the adjoining mines of Woolmet, Carberry, Old- and Newcraighall.

Overgrown slabs of concrete cover what I assume is the site of the buildings above. I can’t figure out where the shafts would have been, and they’re obviously sealed anyway. Dotted across the wasteland are small blue pipes, like periscopes:

How deep they go I can only guess. The two shafts here were the deepest in Scotland. Below where I stand men worked, over 900 metres down. I look up into the sky and try to imagine that distance – the height of a Munro – above me but the blue allows no sense of scale. There’s a chemical odour on the breeze. Barrels seem placed in homage to Paul Nash’s Equivalents for the Megaliths:

Beyond is a curious little domestic tableau. If I wait long enough, will a Beckett play commence?

In 1966 around 40,000 people were employed in the coal-mining industry in Scotland: half of the figure in 1956, but twice the level by the end of the miners’ strike in 1984. Cross-referencing Scottish Collieries with my OS Pathfinder reveals the remains of some 30 mines within a ten-mile radius of Dalkeith.

Monktonhall was mothballed in 1987. Always a wet mine, lying as it did so close to the Forth, the pumps kept working in this fallow period, then in 1993 the co-operative re-opened it. But it wasn’t to last. Despite the optimism of “Monktonhall Colliery: The case for revival“, a survey report commissioned in the late 80s by Lothian Regional Council, Midlothian & East Lothian District Councils, and the NUM, coal had had it’s day in Britain.

“Against advice, a new face…was opened…Water, already a problem in the pit, started to pour in. The entire Lothian coalfield was in effect draining into the pit and the pumps could not cope.”

Monktonhall went into (with grim irony) ‘liquidation’ in 1997. The buildings, including the eye-catching towers, were demolished the following winter. Deep mining in Scotland, but for Longannet in Fife, was finished.

Shawfair’s houses now rise around a perimeter, as if to join forces and converge on this central spot. What will happen to this site I do not know. Although fossil fuel extraction shouldn’t be this country’s future, it is a huge part of the country’s past and should be remembered and recognised as such. The name ‘Monktonhall’ appears on no contemporary map: I hope, as the streets and houses draw closer and the seams of Shawfair join together, it may appear on a future one.

*Riss also designed two mines in Fife whose towers I remember from childhood: Rothes in Thornton, and Seafield in Kirkcaldy.

- If you enjoyed this post, I’ve also taken a cycle ride to uncover the hidden histories of other parts of Midlothian.

Sources:

Ascherson, Neal: Stone Voices (Granta, 2002)

Hutton, Guthrie: Mining the Lothians (Stenlake, 1998)

Oglethorpe, Miles K: Scottish Collieries (RCAHMS, 2006)

Thanks to the National Mining Museum, Newtongrange

Very much enjoyed this Paul. Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We really like your website, it has nice content, Have a great day!

LikeLike

my grandad (charlie wilson) from prestonpans was the 1st miner to die in this pit, i followed in the mining tradition, started in monktonhall in 1976 aged 16, went back in 1993, good solid men who you could rely on when the chips were down.good article thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed this. Researched and well written.

Thank you.

LikeLike