“Politically the UK was still in turmoil, economically the country was very much in the doldrums, and culturally we were still living in the sixties, albeit without any of the verve, and certainly none of the optimism…power cuts and the three-day week…endless public sector strikes, IRA bombings and apparent industrial collapse…it wasn’t exactly a dystopian nightmare…but in 1975, Britain was largely stagnant and dull.” Sweet Dreams: The Story of the New Romantics (Dylan Jones, Faber, 2020)

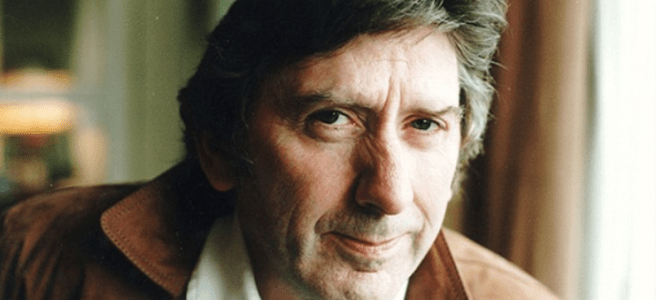

This era of stagnation, financial catastrophe and suppressed anxiety and rage is the background from which James Herbert burst onto the literary scene 50 years ago with his short, sharp debut novel The Rats. No piece of art exists in a vacuum: all are products of their time, and The Rats was very much a product of both time and place. Herbert himself recalled:

‘The subtext of The Rats was successive governments’ neglect of the East End of my childhood: the house I lived in was an old slum that had to be pulled down. On one level it was just a story about mutant rats and people picked it up as schlock-horror. That’s fine with me, but it was packed with metaphor and subtext.’

It may be coincidental that as Herbert’s second novel The Fog was published in 1975, Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservative party; and that the Horror Boom of which he was a major British figurehead lasted throughout her premiership; but that the Horror Boom and Thatcher’s brutal reign also ended at almost the same time – while a case of correlation and not causation – is not insignificant. As Stephen King notes in his overview of the genre, Danse Macabre: “every ten or twenty years [horror stories] seem to enjoy a cycle of increased popularity and visibility. These periods almost always seem to coincide with periods of fairly serious economic and/or political strain”, and by the end of the decade enough had changed, geopolitically, for the surge of interest (and sales) of books marketed as “horror” to tail off, and sharply. That said, the ‘strain’ in Britain was by no means over – there were seven more years of Conservative rule to endure, and another recession – but the end of the Cold War meant that globally, for the first time in decades, the world was not living under the same degree of existential threat.

Although he continued to publish for more than twenty years after the decade ended, it is the 1980s that Herbert is most linked with, and his work often embodies the values of Thatcher’s radical right-wing Conservative government. It isn’t unusual for an artist’s work to reflect attitudes the creator themself doesn’t hold, but Herbert himself maintained he was apolitical. His approach to politics seems to be a disillusioned, even cynical “a plague on both your houses”. However, if you are against both the status quo and progressive politics, aren’t you implicitly on the side of the former? Although in the biography James Herbert: Devil in the Dark Craig Cabell calls Herbert “anti-establishment”, as the last decade of politics has shown us, this does not necessarily make you left-wing. However, the visceral nature of Herbert’s early work in particular overlapped with the sense of frustration in mid-70s Britain that was felt across the political spectrum (of which the equally visceral punk rock was a musical expression).

Herbert’s career to 1990 has two quite distinct phases, but a number of themes are common throughout. The first decade saw a succession of (mostly) short, sharp shockers: novels of around 250 pages. Herbert (like King in the U.S., whose debut Carrie came out the same year) brought horror fiction out of the drawing room and into the street and was explicit in a way no such work had previously been. As Herbert said in a 1993 interview with The Guardian: ”horror novels were written by upper-middle-class writers like Dennis Wheatley. I made horror accessible by writing about working-class characters.” King himself said of Herbert that “he puts his combat boots on and goes out to assault the reader with horror.”

Inevitably, the success of The Rats and The Fog spawned many imitators, but by the mid-80s a younger generation that had grown up with Herbert’s work were pushing the boundaries even further than he had. As a result his own work evolved: he explored different genres and his writing style matured. We’ll look at these later works in Part Two.

***

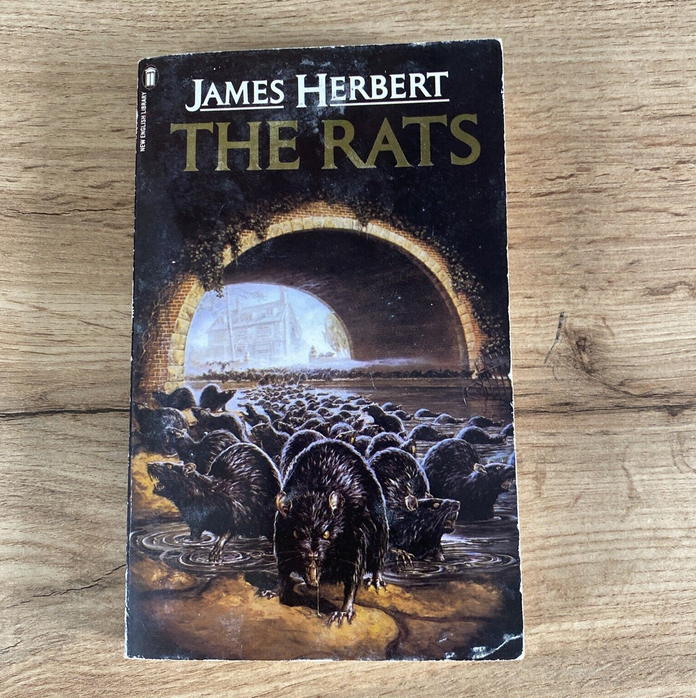

The Rats is dated in many places, and flawed in many others. I hadn’t read it for at least a decade, but was nonetheless pleased to find that it’s still a fresh and exuberant piece of writing, brisk and brutally effective. The first human to be attacked by the mutant rats of the title is devoured on page 9: Herbert doesn’t fuck about.

The set pieces are well-staged: a scene where a group of elderly down-and-outs, slowly drinking themselves to death, are savaged; and another, a stampede-cum-slaughter in a cinema, are particularly gruesome and memorably so.

We get a little back story for the characters who’re about to be devoured, although not in a way that makes us care, as we would with a Stephen King character: just enough to raise them from anonymity.

In The Rats trilogy and The Fog the menace (mutant killer rats; a semi-sentient fog that sends all who breathe its miasma violently insane) is man-made. Neglect or ineptitude on the part of ‘the authorities’ – be they governmental or military – create the ingredients, and a seemingly inevitable societal breakdown allows the effects to be lethal on a massive scale. A constant in Herbert’s work is the role of the individual male in expunging the threat. This is made possible by the lack of communal bonds in the Britain that Herbert portrays. Whereas Stephen King often builds a world

(in works such as Salem’s Lot, Needful Things, and It) which we then see under immense strain until breaking point, with Herbert the breaking point is almost immediate, as if (to paraphrase Thatcher) “there is no such thing as society” in the first place. This individualism was entirely in keeping with the privatisation ethos of Thatcherism, which, in its

ruthless dismantling of Britain’s heavy industries, ensured that previously close-knit (Labour-voting) working-class communities were pulled apart. In Herbert’s books Authority, in whatever form, is no longer the benevolent hand

of Attlee and Bevan but is either malevolent or simply inept, so it’s down to resourceful men (and it is always men) to save the day. As he writes in The Fog “survival…depended on the action of a man. One man.” And as Cabell notes, it’s down to the “man in the street to repair the damage influenced on society by its blundering government agencies”.

Our hero – in the right place at the right time – is schoolteacher Harris, and he is the template for almost every Herbert leading man for the next decade. Curiously, he has no forename (even his girlfriend Judy calls him ‘Harris’), but subtleties like that would just get in the way of the gore. Although someone says to him “you, Harris, are a man of many layers” we get the exact opposite impression: that there is nothing to him other than his actions and the righteous anger that drives them. Herbert’s characters are, for at least the first decade of his publishing career and arguably beyond,

rarely fleshed out more than is necessary for them to act.

Another trope, and much more troubling at five decades’ remove, is the heroes’ predilection for women whose figures are barely post-pubescent:

“Two giggling girls, both in short skirts, both with bouncing breasts, both about fourteen years old, flounced past.

“Anyway, the crumpet’s good.” Harris smiled to himself.”

Although there’s never again anything as creepy as this from our ostensibly sympathetic heroes, they all like women who are of slight build, with small breasts and – in several cases – have (to put it mildly) complex relationships

with their fathers.

I mentioned Harris’s righteous anger, and it’s not a leap to suggest that this anger was also Herbert’s. The neglect mentioned above is what allows the rats to proliferate: “it could only happen in East London…not Hampstead or Kensington.” Harris takes it personally: the (historically poorer) east of the city is “my patch”. Much is made of “the incompetence of ‘authority'”, and there’s anger at post-war architecture and shoddy building practices. The people blame the council for the outbreak (hundreds are dying, eaten alive in tube stations and homes), who in turn blame the government, who sack an Under-Secretary as a scapegoat.

Something else which dates this – and I don’t mean that pejoratively, simply that it tells you which era the book is from – is the attitude to organised labour (indeed, even the mention of organised labour). The 70s was the last era of major (successful) industrial disputes, before Thatcher’s government waged all-out war on union power. The text of The Rats, at least as evinced by the attitude of its protagonists, was unsympathetic: workers “don’t need any more excuses to stay away from work”. These were also the end days (although no-one could have predicted it) of British heavy industry: “dockers earned good money these days, so did factory workers.” The sequel Lair (which we’ll look at below) shares the

same politics: one of the many victims, Terry, is a striking car plant worker, or a “lazy bastard” according to his wife. Harris feels revulsion at seeing people en masse; in Lair one character finds the world frightening because “there were too many strangers”, and it’s not too much of a leap to say that both texts equate the outbreak of rats with crowds of people: symbolised here by the disruptive activity of organised labour. Lone men of action, unobstructed by bureaucracy that threatens to stymie them, see off the rats; after 1979, the year of Lair‘s publication, Margaret Thatcher would similarly handle the unions, who have never since wielded the power and influence they once did.

The root cause of the plague of rats is eventually found, and there’s a human to blame: Professor William Bartlett Schiller, who brought some rats back from an island near New Guinea, which had been used for nuclear testing. The

twin evils then are bureaucracy and/or official neglect, and science out of control, which hark back to 50s B-Movie tropes.

I enjoyed The Rats more than I expected to, having read so many of his books in the research for these pieces and having encountered (time and again) all the tropes which The Rats largely spawned. Although later books are technically more proficient, The Rats is – rightly – what James Herbert will be remembered for and I’d say that, although not the best, it’s the most important and significant British horror novel of the last hundred years.

The Fog was as in tune with the times as his debut: the fog in question feeds on pollution and the book was written at a time of growing environmental awareness, of ‘Save the Whale’ and concern over pesticide use. While Herbert’s work relied heavily on a formula of explicit sex, violence and gore, and can perhaps be better categorised as supernatural thrillers, there are some superbly eerie images in The Fog, including pigeons in Trafalgar Square cooing as one, and silent hordes of people at St Paul’s. The empty London through which the hero Holman travels, while insulated against the insidious fog, is familiar from many apocalyptic 70s TV visions of the capital.

Cabell observes that “his first two novels are evocative of 1950s science fiction, sharing a central male-female team battling against a common enemy in order to return to normality and calm”. There is, however, perhaps a limit to how many horror novels springing from governmental or scientific ineptitude that one author can write. Thus 1977’s The Survivor – Herbert’s third novel – is his first to feature explicitly supernatural elements. Co-pilot Pete Keller is the sole survivor of a Boeing 747 which crashes shortly after take-off from Heathrow, and whose remains (eerily prescient of the 1988 Lockerbie disaster) fall upon nearby Windsor and Eton. Keller’s memory of the moments leading up to the crash are lost, and here we have the first of many Herbert works in which the male lead character has a suppressed

darkness in their past, the unveiling of which is key to solving the mystery they find themselves in. Since the crash, Keller’s sleep has been dreamless: “his mind’s way of protecting him, keeping the nightmare deep within the folds of his subconscious.” Demons are driving local people to extreme acts (murder, suicide); these demons have been raised by the antagonist Goswell, an extreme right-wing former associate of Aleister Crowley.

Nazi magicians (of a sort) also feature in Herbert’s next novel, The Spear (1978), in which a shady, powerful cabal aim to use a holy relic to resurrect Heinrich Himmler. In a Fangoria interview in 1984 Herbert says that The Spear was “aimed at the National Front. They were getting a lot of publicity at the time and their ideas and doctrines were just based on evil and hatred. After it was published they were out to get me for a while. I got death threats, the lot.” Not only that, but he was sued by the author of a book he’d used as part of his research for The Spear and was taken to court.

He had, he continues, never planned a sequel to The Rats, but everything around The Spear had been so distasteful that he needed to write something “that wasn’t too heavy”. The result was Lair (1979).

Set four years after the events (“the Outbreak”) of The Rats, the novel’s prologue – rather neatly – is also the epilogue to The Rats. Herbert is more measured in his plotting now, and there are similarities to Jaws 2, in which nobody believes Chief Brody’s warnings that the menace has returned. Once again, bureaucracy gets in the way of action. Herbert builds

tension, firstly by establishing the setting (Epping Forest) creating a sense of claustrophobia (we rarely see beyond the trees and paths of the forest), then by delaying the inevitable. In The Rats as mentioned above, the first person is eaten alive on page 9. In Lair, it’s page 89, a third of the way into the book. The beasts are glimpsed, or heard, without making

themselves evident.

Our hero this time is Lucas “Luke” Pender (are forename and nickname a nod to Star Wars?), who, in being an actual ratcatcher, is better-equipped than the victim-of-circumstance Harris. We find out only much later that he has a vendetta – his family was killed by rats in the previous Outbreak. That’s his sole motivation, and we know little else about him.

How do you tell a story of a plague of mutant rats twice? Well, in Jaws 2 the shark was female: larger and deadlier than the male (according to the publicity, at least). In Lair, Herbert makes the rats smarter. In the original outbreak, mutants mated with normal black rats. This time the threat is from “the purer strain”. Their numbers are fewer, but they’re

cleverer.

***

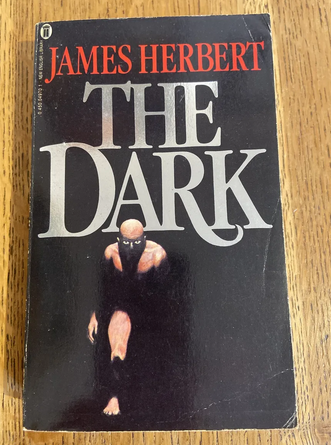

Herbert began the 1980s with The Dark (1980) which is in many ways a rewriting of The Fog but (like The Spear) as a supernatural thriller. The hero of The Dark is Chris Bishop (a prototype for Herbert’s recurring paranormal investigator

David Ash) and he conforms to what is by now the standard Herbert template for leading men. Almost without exception they are referred to by their two-syllable surname, chosen to evoke a sense of strength: Harris (The Rats);

Holman (The Spear); Culver (Domain), etc. These men are always single (which frees them to have sex with the female lead), and as Herbert’s career progressed they increasingly had a repressed past as the result of some distant family trauma. They are often either ex-cops or ex-military; tend to dress in leather jackets (like Herbert himself), and are generally 30-something white cis males. In addition, they like a “stiff drink” of scotch; eat steak; smoke fags; and the repressed trauma means they have skeletons in their closets (along with the leather jackets): “tears were a luxury he hadn’t enjoyed for many, many years” (The Dark); “memories…better left dormant” (Moon); “my past has got nothing to do with what’s happening now!” (Moon, again, illustrating the denial that prevents the heroes from properly acknowledging the threat).

The hero of The Spear, the aptly-named Steadman is characterised as follows: “rebel would be too romantic [a term]…oddball not quite correct. Let’s just say team spirit was not one of your finer points” and this is true for almost all of his protagonists. “I’ve told you who I am”, says Steadman “You’ve told me what you are” comes the response, to which Steadman retorts “what I am is who I am”: this is the key to Herbert’s cipher-like, largely interchangeable heroes. Although after his earlier books this trope of a repressed past adds a degree of depth to his leads, it isn’t until 1990’s Creed, in which the eponymous paparazzo is a sleazy anti-hero, that he moves away from this model.

But to return to The Dark: the threat is exactly that: a tangible darkness that spreads from a particular house, itself the scene of violent trauma. It’s a grim read, the horrors (including a spectacular scene of violence at a football match) unleavened either by black humour or the usual sex between the two leads. The precise nature of the Dark is never entirely explained – is it chemical, or a manifestation of Evil? – and the climax sees resolution thanks to a convenient deus ex machina. Like The Jonah (below) working class people are right-wing and tend to speak in dialect.

Jessica, the female lead, has a complex (almost incestuous) relationship with her blind father. Women in Herbert’s fiction, as I mentioned above, tend to be attractive and young – sometimes with a vulnerability and physical build (small breasts) which is almost adolescent. Others, such as spouse-poisoner Emily in The Survivor, or Cora in Sepulchre have a need to be dominated. For those women – usually those over thirty – who are not attractive to the male lead, the epithet “plump” is applied, rendering them harmless and/or irrelevant. The sex scenes were a key part of Herbert’s appeal and were in no small part responsible for his popularity among that demographic normally least-likely to be found with their nose in a book: adolescent males. Like the slasher films of the 80s, the Guardian observed, “the sex in his novels follows a…system of vigilante justice. Casual sex is ridiculed; violent sex is punished: ‘I don’t have monsters tearing off girls’ clothes. But in Domain a girl was raped and the guy who did it was eaten up by a monster.’ Typically…romantic love redeems the loner hero.”

The Jonah (1981), described by Cabell as “stark” and “melancholy”, although far from being his most famous book is in many ways a perfect example of a James Herbert novel, because it contains almost all of the tropes and traits found in his work. Although I used the word “formula” above, it was a phenomenally successful one which many aspiring young horror writers (myself included) tried unsuccessfully to copy.

Working undercover, hero Jim Kelso is sent to a Suffolk backwater to infiltrate and uncover a drugs ring. He has a reputation as a Jonah, or jinx, bringing bad luck to his investigations or those people he gets too close to. We see snapshots of his youth (and indeed his birth) in which there is always a spectre lurking just out of sight. That shadow is his twin sister, and the reasons for her evil nature seems to be that she is “ugly, deformed”, which is no advance on Tolkien equating ‘Orcs + black skin = evil’. Naturally, Kelso meets and has explicitly-detailed sex with the female lead; his repressed memories take him to the edge of breakdown, and he ultimately destroys or banishes whatever character embodies the Other. Unusually for Herbert, Kelso is given the opportunity to embrace the Other here, but rejects it. The Jonah, though, like much of Herbert’s work, is highly readable, and the climactic flood is brilliantly-realised. We also see snapshots of locals’ lives shattered as the waters engulf the coastal town.

What else can we glean from The Jonah? We read of aspirational “socially mobile C2s” who are “moving away from their origins…with more idea of what they want” which captures the spirit – indeed the ideal – of early Thatcherism. In a flashback to 1950 a toilet attendant rages against “soddin’ Attlee and his Welfare State”, and although the reader may think “fair enough, it’s only one character’s opinion”, when there’s no balancing voice from the other end of the

political spectrum in the entire book to throw that opinion into relief, it’s hard to escape the feeling that the author – or at least the text – sympathises. Indeed, every character embodies a slightly different right-wing viewpoint, from the ennobled arch-capitalist to the law-and-order freak, via the xenophobic fisherman. With this in mind, it’s perhaps unsurprising that, as Herbert told biographer Cabell, “my books are very popular…in the Armed Forces – the police force”.

The Jonah also displays – and this is no exception in Herbert’s work – an encyclopaedic level of research, which unfortunately often reads like it: it isn’t worn lightly. Lair, for example, includes lines of dialogue that are weighed down by it: “But alpha-chloralose, coumatetralyl and chlorophacinone haven’t been fully tested against them yet.” Just try reading that line out aloud. Written nowadays we’d say there was a “distinct smell of Google”.

His next novel was his longest to date. Shrine is the story of eleven-year-old Alice Pagett, who, unable to hear or speak since early childhood, is miraculously cured after what she describes as a visitation from the Virgin Mary. Alice in turn performs cures on the sick, and hundreds flock to the spot where she had her vision. The hero this time is local journalist Gerry Fenn, a prototype for the later hero of Creed, and who – although a walking hangover – is rational enough to be sceptical about the events, whilst simultaneously aware that (as the man on the spot right from the

outset) they offer him his ticket to greater things. In places Shrine – which for the first time shows a more complex structure and has subplots – is far better than anything Herbert had written up to this point. The sense that all is not well – that there’s something awfully wrong with Alice – is drip-fed nicely, creating a sense of tension and creepiness often absent from his work. It suffers from the usual flaws, and Herbert’s attempts at representing the internal monologues of his characters (in particular the dangerous obsessive Wilkes) are clumsy and dated, but the huge amount of research which such a novel required is – for a change – lightly worn, and woven into the text quite smoothly.

Shrine shows greater ambition, too. It attacks the hypocrisy and empty ritual of organised religion (specifically the Catholic Church). It’s also the closest he comes in this period to creating a sense of community – the village of Banfield – being torn apart by various forces (the focus of the world’s media; the clamouring pilgrims; and the unscrupulous businessmen looking to make a quick buck). But it’s not entirely successful because unlike Stephen King Herbert does it without making you care about anyone: Fenn is an outsider, and the only insiders we see are either on the make or in the centre of the storm.

In some ways his next book Domain – the final book in the Rats trilogy – is a step backwards; not simply because in it Herbert reverts to writing once again about his furry antagonists but because this book, almost as long as The Rats and Lair combined, is structurally less ambitious than Shrine, which had shown that he could successfully handle subplots. That said, there’s certainly no lack of ambition in terms of scale: the first two dozen pages sees London obliterated by a series of nuclear attacks. Herbert has lots of fun vaporizing Londoners of all stripes and laying waste to landmarks left, right and centre. Indeed the opening is as (excuse the pun) bombastic as any 80s action thriller. And, just as everything got bigger and brasher in the mid-80s, Herbert ups the ante: not only do we have the very zeitgeisty nuclear Armageddon (once again horribly relevant), but the rats don’t just have a “lair” anymore: they’ve inherited an entire “domain”.

Like The Jonah, the research lies heavy on the page and I’m not sure the reader would suffer if there was less information about the construction and layout of secret bunkers underneath London, but despite this Domain still rips along at a faster pace than any previous Herbert novel.

Our hero is Steve Culver who, in his “leather jacket and jeans”, is interchangeable with most other of Herbert’s leads. Again, he represses his emotions because of a traumatic experience in the past (as a helicopter pilot, he once crashed into the sea, killing most of his passengers): “push it away, Culver, save it for later”; and his relationship with the female lead Kate is what heals him. We’re told that “Culver’s impassivity paradoxically conceals an intensity of feeling”, but there’s no paradox here; as we’ve seen in every other book, Herbert is incapable of evoking the reader’s empathy, and the emptiness is just that.

Like Harris in The Rats, Culver is the right man in the right place. By a stroke of fortune he survives the initial blast and is led by government minion Dealey into an official underground shelter. However the small band of survivors there must flee when it’s flooded by both rain and rats, and their stumbling journey through the wreckage of the city (“the familiar London landscape…no longer existed”) is episodic and under-structured, as if Herbert’s plan – and it may be a valid one – was simply to see where their journey would take them.

Interestingly, the most affecting scene in the novel – and arguably one of the best scenes in any of his books – comes when the group stumble upon the aftermath of a rat attack in the central control room of the government headquarters. The characters have to piece together what must have happened, and this distance – and the lack of detailed description – is what gives the scene its unsettling power.

The band is whittled down: by angry, radiation-sick survivors and of course by the new larger, smarter, mutated rodents, until in the final scene Dealey is sacrificed so that Kate – whose hand Culver has amputated to save her from a rat – and Culver himself, physically unscathed – can be winched to the safety of a helicopter. Physically unscathed Culver may be, but it’s at this point that (unlike the previous heroes) he snaps, and the story ends with his hysterics about to be sedated by a needle. A pessimistic coda reveals that the rats have mutated to a point where their newest generation shows distinctly human form, and that the world is now their domain.

Domain may have revisited past horrors, but it also served as an ending to the first phase of Herbert’s career. By now, the mid-80s, a younger generation was pushing the levels of explicit gore and sex in horror fiction to even more extreme levels, exemplified by those writers grouped under the ‘splatterpunk’ tag (which included, but didn’t even begin to define the depth of work produced by, Clive Barker), and – less punk, more heavy metal – Shaun Hutson. In many ways Hutson took Herbert’s formula and injected it with stimulants. The only way for the older, established – and by now semi-respectable – Herbert to respond was to not compete. From the mid-80s his books become smaller and more intimate in scale. There are neither rodent apocalypses nor sentient murk.

Sources

by James Herbert:

The Rats (New English Library, 1975)

The Fog (New English Library, 1976)

The Survivor (New English Library, 1977)

The Spear (New English Library, 1979)

Lair (New English Library, 1980)

The Dark (New English Library, 1981)

The Jonah (New English Library, 1981)

Shrine (New English Library, 1983)

Domain (New English Library, 1984)

Jones, Stephen (ed.) – James Herbert: By Horror Haunted (New English Library, 1992)

Cabell, Craig – James Herbert: Devil in the Dark (Metro Books, 2003)

Jones, Dylan – Sweet Dreams: The Story of the New Romantics (Faber, 2020)

Hendrix, Grady – Paperbacks from Hell (Quirk Books, 2017)

Fangoria, January 1984 (interview by Martin Coxhead)

image (c) Pan Macmillan

3 thoughts on “Horror Rewind special: James Herbert! (part one)”