Islay

My friend Dave and I recently celebrated our joint 50th birthdays by spending a long weekend on Islay. Where’s Islay, some of you may ask? Here’s Islay:

And it’s pronounced “eye-lah”. Not “eye-lay”, “iz-lay”, or “ill-ay”. Eye-lah. It’s famous – properly world-famous – for its whisky, particularly smoky, peated, single malt scotch whisky from one of the ten (ten!) distilleries on the island (with more in development).

Islay feels properly Hebridean, and far more northern and western than it actually is. We could see the coast of County Antrim, and although heading west there’s no land until Canada it’s on the same latitude as – and as the crow flies, only 100 kilometres or so from – Glasgow.

It’s an island that feels both large – the expanses of peat bog and low mountains seem vast, with few buildings to give them scale – and small: you can drive across it in forty minutes or so.

From the ferry at Port Ellen we headed to the island’s north-eastern corner, where three distilleries cling to the narrow shoreline overlooking the Sound of Islay north of Port Askaig. The view is stunning, almost overwhelming; but curiously, the main feature and the most obvious geographical features you’ll see when on Islay, aren’t on Islay. The paps of Jura (of which, unusually for paps – breasts – there are three) are far higher than Islay’s highest peak and loom in the distance from almost every spot.

Up here are Caol Ila (“Cull Eela”), the brand-new Ardnahoe (nice cafe; their inaugural release of whisky was, however, beyond my budget); and Bunnahabhain (“Boona-hav’n”). When we arrived, the sky was blue, there was no wind (even allowing for the fact that the cliffs that these distilleries shelter under protects them from the prevailing westerlies), and the tide stroked the pebbles on the Bunnahabhain shoreline with a breathy crackle.

The distilleries all have a visitor centre of some sort; all have a shop; some have a cafe or even (Caol Ila, Ardbeg) a restaurant. The owning companies know that people come here in their thousands, and while the quality of “experience” varies, all of them offer one. They also offer a dram when you walk in: while some may offer you one of the distillery’s signature range (such as you can buy in your local supermarket), others will offer you something you’ll only get then and there – something older, rare, and correspondingly expensive. They can afford to dish out drams that would cost you £20 in a bar because they know enough people will buy a bottle1. Drivers are offered a bottled “driver’s dram” to take away so no-one need miss out.

On Saturday the weather was unchanged and the island’s largest town, Bowmore, was dazzling in the sunlight. The eponymous distillery is the oldest on Islay but the visitor centre felt blandly corporate. By contrast, the Celtic House just across the square is one of those wonderfully quirky emporia found in the Highlands and Islands which is (and indeed has to be) all things to all people: a bookshop, giftshop, cafe, you name it. From the pier at Bowmore you look across Loch Indaal to the Rhinns: the westerly arm of the island. In the faint haze it looks a long drive away but we got there in fifteen minutes: distances are deceptive on Islay.

We headed then to Kilchoman. It’s the only distillery not on the coast. I’d had a bottle before and because I knew it was recently-established (2005) my expectations were not high: part of me felt it couldn’t be “truly” Islay. Wrong, wrong, wrong. Kilchoman is wonderful2.

We fell in love with it. It’s a friendly, welcoming place, hidden away along a winding, narrow, single-track road almost as far west as you can go, and the view over Machir Bay is gorgeous. Looking at a map it would be the one you’d think “we could give it a miss” if pushed for time, but you’d be making a mistake.

A series of information panels details each year’s history with a disarming candidness and charm not on display elsewhere: after all, this is the only independent distillery on the island, family-owned and -run since inception, and not controlled by a distant multinational. What’s more they do it all on Islay: grow their own barley and malt it; then distil, store and bottle all on-site. With reason and pride they can name one of their bottlings “100% Islay”.

The next stop is Bruichladdich (“Brook-laddie”), whose sky-blue-and-white buildings are blinding in the mid-day sun. Bruichladdich was, for a time early in this century, the rogue, punk distillery on a mission to shake up an industry it saw as weighed down by tradition, and a drink it saw as associated with wealthy, middle-aged white men. Although now owned by Rémy Cointreau it still has a swagger, and proudly proclaims itself a “Progressive Hebridean Distiller” in more ways than one, having made steps to become more sustainable and ethically responsible (it’s a B Corp employer).

But, lovely as the softer Rhinns are, we have an appointment to keep: a distillery tour at Lagavulin. The tour begins with a dram, and ends with another three, and takes us around the production facilities from the long-unused kiln for peating malt, to the distilled spirit. Afterward, we explore Lagavulin Bay, whose two encircling arms are topped by, on the eastern side the ruins of Dunyvaig Castle, ancient home of the Lord of the Isles; and on the western side the indiscernible location of an Iron Age fort.

We had also stopped off the previous day at Finlaggan. Now a quiet loch, where a walkway takes you to a small island of scattered stone ruins, this was for centuries the spot from which a third of the Scottish landmass was ruled. Islay was once a major power in this part of the world, whose power only dwindled as what we now know as modern Scotland coalesced. But megaliths across the island speak of inhabitation stretching back millenia.

And there are plenty other signs which show that the 3,000 or so who inhabit the island today are far outnumbered by the dead: there are ruined churches at Kilchoman and on the peninsula of the Oa, speaking of former communities which potato blight, poverty or forced clearance have destroyed.

Just as poignant are the memorials: not only the war memorials familiar across the continent – the Highlands and Islands lost proportionally more young men than anywhere else in the country – but the two monuments commemorating very specific events: the sinking, within six months of each other, of the SS Tuscania and HMS Otranto. Over 600 lives were lost in total. Above Machir Bay stands an American cemetery where the dead of the latter disaster lie, and at the tip of the Oa is the striking American monument.

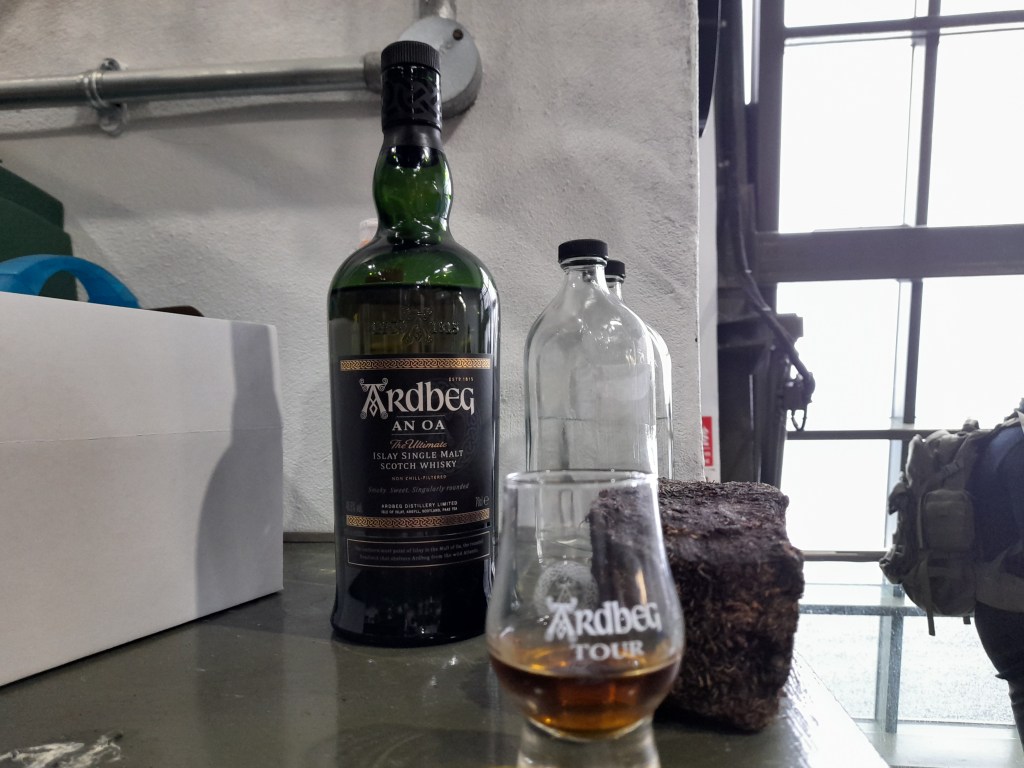

The final rendezvous of the weekend was our second distillery tour. Ardbeg manages to walk a fine line; on the one hand, the guide was repeatedly very clear that innovation was not what they were about: “doing what we did yesterday” is their motto. And this cleaving to tradition is far from unusual in the world of whisky: after all, so much of its image is founded upon age, heritage and doing things a certain way: a small “c” conservatism, if you like. But at the same time, Ardbeg is the closest whisky gets to a cult, and its marketing, bottling, and the branding within the visitor centre are all decidedly quirky and, dare I say it (given the context), radical.

Thus ended our brief tour of the whisky island. Yes, we paid for a couple of tours, spent money in every single distillery, had a fish supper, paid for accommodation, etc. But what impact does whisky tourism have on a small (and fragile) infrastructure? Writer Andrew Jefford is clear: “few profits…find their way back”. The Scotch Whisky Association, unsurprisingly, sings a different song. Their figures for 20223 claim that the visitor spend across distillery visitor centres Scotland is £85million. There are (again, according to the SWA) 151 distilleries of one form or another in the country – not all of which will have a visitor centre – so that works out at over half a million per year per distillery, or £5million on Islay alone. They also claim that over 1,100 people are employed at visitor centres (presumably not counting the people distilling the actual whisky), which averages just over 7 people per distillery, or (on Islay) a total of around 60 jobs.

Whisky

Geology is the foundation – literally and metaphorically – of our lives. The rocks beneath us determine what grows above them – whether the soil will be acid or alkaline – and the water that passes over (or through) them. As far as whisky is concerned, that means “will barley grow locally, or does it need brought to the distillery?” It will also have an impact on the water.

Marketing departments want you to believe that a whisky is the expression of a particular place: that, like wine, we can speak of terroir. But to what extent is this true?

First things first. Whisky is made from three ingredients: barley, yeast and water. For most distilleries in Scotland, the barley is not grown on-site and comes pre-malted from elsewhere: from Aberdeenshire, East Lothian or even (whisper it) England. If you look at a map of barley-growing areas in the U.K. they’re mostly in the east, because of the drier climate.

Islay is in the west of Scotland, and doesn’t have an ideal climate for cereal crops, so to what extent is the barley used by the Islay distilleries local? According to Ian Wisniewski, in his A Passion for Whisky, “19 farmers” across the island grow barley for Bruichladdich, “enabling 45% of production in 2020 to be locally grown”. Unless you’re near Kilchoman (who grow enough to supply a quarter of their needs), chances are any barley you see growing is destined for Bruichladdich. But this still represents a very small percentage of Islay whisky production being made from island-grown crops.

Although Bowmore, Kilchoman and Laphroaig malt at least some of their own, the huge Port Ellen maltings processes the barley to each distillers’ specifications: typically, this means catering for the different levels of peat that each distillery demands. It’s this peat smoke that provides Islay whisky’s characteristically pungent, smoky smell and taste.

The strain of barley affects the flavour, too, and different strains grow better or worse in different conditions, offering up varying yields and thus rising and falling in popularity as a result. For example, Wisniewski quotes Kilchoman owner Anthony Willis, for whom the strain ‘Sassy’ “produced [a] richer, creamier character” than ‘Concerto’.

So much for the barley, and if we accept that yeast is not produced locally, what of whisky’s third and final ingredient, water?

The quartzite rock which forms much of Islay’s bedrock is impervious, and so the water (except for Bunnahabhain, whose source is a peatless spring) runs from lochs or lochans and, tinged with the colour of the island’s expansive peat bogs, absorbs few minerals and is, consequently, soft. But does it contribute to the spirit’s flavour?

I have beside me as I write, the box that contained a bottle of Laphroaig 10 year old, and it talks of releasing “the heathery perfume of Islay’s streams”. However, Andrew Jefford, in his Peat Smoke and Spirit asks industry experts for their view on water’s contribution to the taste and finds “the biggest myth that we, as an industry, have perpetrated” according to one; “baloney” reckons another. A third, asked for their view on the effect, estimates “on a scale of one to one hundred…between one and two.” Ian Wisniewski speaks of the “emotional impact” on the drinker – magical thinking, if you like – of the local water.

If water plays a negligible part, then what of the distillation process? Jefford defines terroir as a “profoundly local and individuated matrix of soil, topography, climate and custom”, and we’ve looked at the first three elements. The final one – custom, the distilling process itself – must surely play a vital role?

The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 define the classification of single malt scotch whisky, and point to “distinct flavours and characteristics that are influenced by the specific distillery’s production methods and location.”

There are multiple – almost infinite – factors which influence the flavour of new-make spirit. The length of fermentation – the process of creating the beer-like ‘wort’ which is then distilled into spirit – differs from distillery to distillery. The wash and spirit stills that the double distillation process occurs in also differ: a larger still, or a still less-charged (less full) than another, will result in a lighter-tasting spirit, because the heavier congeners (which carry the flavour) find it harder to rise, and also because the greater the contact with copper, the more elements are ‘trapped’ by the metal. Stills differ in size and shape from one distillery to the next, and this is a key reason why Laphroaig tastes different from Lagavulin, which tastes different from Ardbeg, and so on, even though each distillery is only a kilometre or so from the next.

The next stage that influences flavour is the “cut”. The first vapours that rise and condense into liquid contain toxins (not least methanol, which will make you go blind if you drink it), and the distillers will let these go, judging the right moment to begin to store the spirit that is being produced. If they wait too long, certain flavours will be lost. If they then leave the “cut” for too long, then the heavier flavours have had a chance to find their way into the spirit and the longer they run, the more unpleasant they taste. So the points at which the “cut” is made – on and then off again – have a huge role in determining the taste of the new-make.

But what is this “new-make” that I’m talking about? Well, those same Scotch Whisky Regulations stipulate that this spirit cannot be called “whisky” until it has spent three years maturing in oak casks.

And here’s a thing. They aren’t stored in fresh oak: they’re stored in casks which have typically previously held bourbon or sherry. The flavours of these previous contents impart themselves into the spirit. And although this leads to a wonderful array of aromas and taste sensations, it can’t quite hide the fact that much of whisky’s character comes from the influence of other alcoholic drinks.

And where do these casks spend their three (or five, or ten, or twelve, or eighteen) years maturing? Some are stored on Islay, either in old-fashioned “dunnage” warehouses, cool, damp and dark; or giant, modern racked warehouses, like those at Bruichladdich and Laphroaig.

We’ve seen how the ingredients and distillation can (or can’t) influence the flavour: does where they mature add anything to their taste? No-one is quite sure, and I think that’s a good thing.

Wisniewski quotes the Bruichladdich distiller (“I find a maritime element due to the location the barley is grown in – there is an element of sea spray in the soil. And maturing on the island gives all the casks a maritime character”), but is even-handed himself: “sea salt and brine on the palate… ‘it’s from the peat’ say some. ‘It’s sea air entering the cask’ say others. And, of course, it could be both.” The doyen of whisky writers, Charles Maclean, is certain that storage in these maritime conditions “influences the flavour of the whisky matured under these conditions”

But Islay simply isn’t big enough to host all the spirit produced there. A representative from Diageo, who own Lagavulin (among others), the majority of which matures in central Scotland, by contrast stresses that it’s “irrelevant where Lagavulin is warehoused.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, our Lagavulin tour guide was adamant that because “Scotland’s a small country” there’s little real variation in climate and that therefore the location of the casks doesn’t matter. But that isn’t quite the case, or – as we’ve seen – barley would grow in the west.

Andrew Jefford is uneasy that “every drop of spirit distilled at Caol Ila is now trucked off the island in bulk, and doesn’t meet wood until it settles down on the Scottish mainland” where it will stay for at least 12 years. To what extent can this drink – which has, true, been created on Islay, even if the barley is from elsewhere – which has spent a mere fortnight on the island, truly be called a product of a particular place?

And yet, there is a sort of magic inherent in whisky. As we’ve seen, a huge number of variables mean distilleries that are practically next door to one another will produce very different spirit. Although my palate isn’t as sensitive as that of a conoisseur, even I can pick up a dozen or more of the 70-100 different flavours that have been identified in malt whiskies. And yet there are only three ingredients. How is that possible? Well, that’s where the magic happens. There is no toffee, or liquorice, or raisins, or spice, or chocolate – yet sample a few malts and you’ll encounter any number of them, whether on the nose, rising from the glass, or on your tongue or soft palate; or afterwards, as the “finish” ends one dram and beckons you to another. We are all different; each of us has a distinct set of memories and associations that particular aromas will awaken, meaning that the same whisky will differ for every drinker. Try some for yourself and find out.

Notes

1At Ardbeg, one of the party of boisterous young Dutch guys on the tour with us did just that, snapping up a £550 limited edition. They also wanted a branded water pipette (“just give them one”, said the exasperated tour guide to the shop assistant), and even the tour guide’s branded bag (“No”).

2The art of distilling came to Scotland via Irish monks, for whom Islay was probably their first landfall, in the 13th or 14th century, possibly at Kilchoman. Much as I loved Kilchoman, as a native of Newburgh I feel duty-bound to put in a word for the fine Lindores Abbey Distillery which claims to be the home of whisky (the first written record of distilling appears there, from 1494).

3Quoted in Cask & Still Magazine, issue 17

Sources

Jefford, Andrew: Peat Smoke and Spirit: A Portrait of Islay and its Whiskies (Headline, 2004)

Maclean, Charles: Spirit of Place (Frances Lincoln, 2015)

Wisniewski, Ian: A Passion for Whisky: How the Tiny Scottish Island of Islay Creates Malts that Captivate the World (Mitchell Beazley, 2023)

Cask & Still, issue 17