Earlier this year I happened across the 1980 Asterix annual in a charity shop; a book whose existence I was entirely unaware of. It was evidently a one-off, and provides an introduction to many of the long-running French comic series’ characters, along with heavily abridged versions of some of the stories, and the usual puzzles and games you’d expect to find in a children’s annual. Most of you are no doubt familiar with Asterix: the eponymous Gaulish warrior whose village holds out against Julius Caesar’s roman invaders in 50 B.C. The stories were written by René Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo and offer a wry, often bitingly satirical look at contemporary postwar French and European culture. But don’t for a minute assume that they’re just for kids: we all know books and films that are ostensibly for children but who have references that go way over their young heads, and so it is with Asterix.

The real draw of the annual – a very rare Asterix item, it turns out – is a bande dessinée version of the film The Twelve Tasks of Asterix, which exists nowhere else in English. There was, at the time, a book of the film: a text story supplemented by scenes from the animation. This, though, reads like an actual Asterix strip, though the artwork is closer to that of the film than to that of Uderzo, and the translation doesn’t read like the regular English translators, Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge, of whom more anon.

This volume is a reminder that Asterix’s journey in Britain (and I don’t mean Asterix in Britain) is a more convoluted one than the nice uniform white volumes you can buy today – or even an old 70s or 80s album – would suggest.

The strip’s first appearance was as a serial in Pilote1 magazine, and in the early albums you can still see how the page layout was tailored to that format. The first Asterix book that we all know in the familiar large-scale album format – Asterix le Gaulois – was published in 1961 by Dargaud in France. The strip’s popularity grew enormously through the early 60s and it was only in the mid-70s, after a fall-out with Dargaud, that an Asterix adventure appeared (Caesar’s Gift) as an album without having first been serialised.

In the U.K. Asterix the Gaul appeared in 1969, published by Brockhampton Press and translated by Bell and Hockridge, whose immense skill as translators became evident as the series progressed. But this wasn’t Asterix’s first – or even his second – appearance in Britain.

Valiant had printed their translation of Asterix le Gaulois as ‘Little Fred and Big Ed’ (later ‘Little Fred, the Ancient Brit with Bags of Grit’) on the comic’s back page in 1963-64. A year or so later, Ranger comic printed ‘Britons Never, Never, Never Shall Be Slaves!’ [Asterix and the Big Fight], featuring heroes Beric and Son of Boadicea (yes, really) in place of Asterix and Obelix, and rather awkwardly transplanting the entire comic’s world into Roman Britain. See this page or this page for more info.

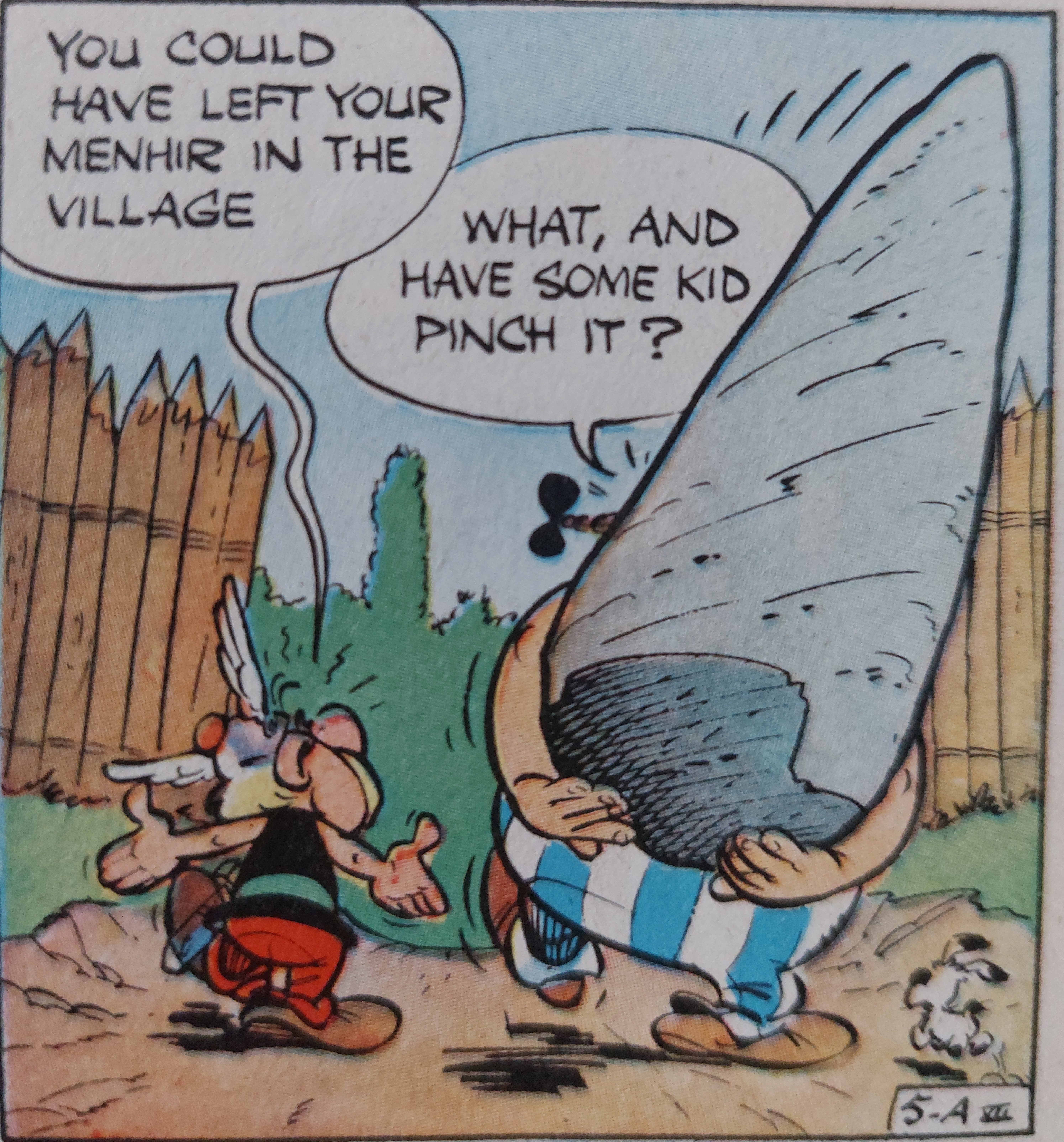

Although Tintin had been popular in Britain for years, it was 1969 before the series considered “too French” or “untranslatable” was indeed translated (and how), when the small Leciester publisher Brockhampton Press engaged Hockridge to squeeze every cultural reference out of Goscinny’s work, and Bell to translate the text into English. Indeed, so crammed with references are the originals – some of them, indeed, untranslatable, or at best meaningless to an audience outwith France – that the English translations must surely rank as some of the least literally faithful but simultaneously finest-ever works of translation ever undertaken. Bell & Hockridge’s ability to find apposite puns and quips while staying true to the feel and sense of the original is phenomenal. Compare this frame from Big Fight as translated by Valiant comic, and then by Bell & Hockridge:

The joke’s the same, but I know which one is funnier.

Brockhampton’s decision to start with Asterix the Gaul made sense: it introduces us to the world of this tiny Gaulish village that holds out against the (often hapless) Roman invaders thanks to the magic potion which gives them temporary superhuman strength. In the first volume we meet the fierce and cunning warrior Asterix, his slow-witted but lovable giant menhir-delivering companion Obelix, village bard Cacofonix, their chief Vitalstatistix, and the wise, shrewd and downright laconic druid Getafix.

By and large, there are two types of Asterix adventure. There’s the “village in peril”, where an external force arises to threaten the Gauls’ solidarity (Obelix & Co, Caesar’s Gift, Soothsayer, Roman Agent, The Mansions of the Gods, etc.); and there’s a quest in the form of Asterix in… where our three heroes (I’m counting Dogmatix) travel to a neighbouring country – of which France has many – in order to aid local resistance to the Romans, help out a friend or distant relative, perform some heroic deed, or, er, participate in the Olympics (Switzerland, Spain, Britain, Cleopatra, Olympic Games, etc.). But Goscinny was no chauvinist, and no doubt delighted his native readers by sending up the French, too (Banquet, Chieftain’s Shield, Corsica).

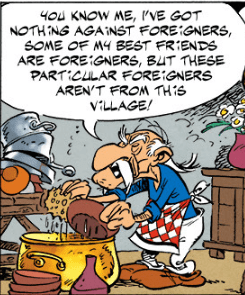

As Goscinny got into his groove through the mid-60s, the dramatis personae expanded to include figures whose names in English we can thank Bell & Hockridge for, such as village blacksmith Fulliautomix and his best frenemy, Unghygienix the fishmonger; Unhygienix’s wife Bacteria; Vitalstatistix’s feisty spouse Impedimenta, and the fiery xenophobe, Geriatrix:

Brockhampton’s publishing strategy thereafter, however, makes less sense2. Their 2nd volume – and how were British readers to know it was actually the 14th? – was the recently-published Asterix in Spain, followed by the 8th volume, and the one most likely to appeal to an audience on this side of la Manche: Asterix in Britain. Afterward, there seemed no logical pattern to the order in which volumes were translated, right up until the 24th volume – Asterix in Belgium – when the U.K. series finally began to run in parallel with the French.

The large-scale albums (21.5 x 29 cm) that modern-day readers are familiar with weren’t always the only format. Knight Books published all the adventures up to the mid-80s in a small (15 x 20cm) format, which were a handy size and even if the artwork and text were necessarily smaller, they’re still nice editions. More curious – in fact, verging on the bizarre – was their decision to also print eight of the books in a standard paperback size, with the artwork oriented 90 degrees, making for an unsatisfactory – if quirky – reading experience: “Now turn the book sideways and read on”.

Much of the fun of Asterix is in the pun-based character names, and sometimes Bell & Hockridge improved on the original. Goscinny’s bard is Assurancetourix (assurance tous risques / fully-comprehensive [motor] insurance) which is good, but given how awful his musical ability is, it’s not a patch on Cacofonix. Roman names ending in the suffix -us give lots of room for wordplay, with characters called such delightful things as Crismus Bonus and Egganlettus, not to mention the architect Squareonthehypotenus3. Obelix’s dog is called Idéfix in the French, from idée fixe – fixed idea, or dogma – which lent itself with serendipity to Dogmatix. The album titles in the U.K. are more literal and tend to have “Asterix” in the title, presumably because they have to work a bit harder to sell themselves than in their native France. Compare:

- La Serpe d’or – Asterix and the Golden Sickle

- Le combat des chefs – Asterix and the Big Fight

- Le bouclier Arverne – Asterix and the Chieftain’s Shield

- La Zizanie – Asterix and the Roman Agent

Bell & Hockridge skilfully found Anglophone alternatives for names or references that wouldn’t work outside France. In Asterix the Legionary (one of the funniest books I know) the Gauls’ perennial whipping boys – a luckless band of pirates – are once again left shipwrecked after a skirmish with Asterix and Obelix. Uderzo’s illustration of them clinging to the remains of their ship is a direct parody of The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault. In the orginal French, the bearded pirate leader sighs “Je suis médusé”, while in English this is rendered as “we’ve been framed, by Jericho.” This page covers this particular panel and more of the genius of Bell & Hockridge in further detail. Asterix in Britain is a really interesting case in point: my son has both it and the French original (Asterix chez les Bretons) and you can see how many changes Bell & Hockridge were forced to make because of what’s lost in translation. For instance, when Goscinny’s British talk, the adjective comes before the noun, unlike in French. In an English translation, where everyone talks like that anyway, it obviously wouldn’t work so you lose the cleverness of a sentence like “ce n’est pas la magique potion” which would sound unusual and therefore funny to a Francophone readership; the equivalent in English would be “it not is the potion magic”. Obelix, ever a quick learner(!) uses such sentence structure throughout (“chien petit” [sic], “la romaine galère”).

Some of these translations have become dated, and there are many references to Latin which assumes the average British schoolchild is taught the language. David Bellos, in his masterful guide to the work of translators Is that a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything convincingly argues that translations need updating: or rather, that translations date in a way that the original work doesn’t, and so each generation will need a new translation. Controversial to say, but there’s much about Bell & Hockridge which would benefit from being quietly modernised to ensure a continued young audience for these books. That said, one of the delights of re-reading the books as an adult is spotting references I didn’t get as a kid, when there was neither Google nor or online annotations.

Goscinny (also author of Lucky Luke, Iznogoud, and the excellent, wry, Nicolas novels) died at the tragically young age of 51, midway through the writing of Asterix in Belgium, and you can spot the exact point at which it happened, because thereafter Uderzo’s Belgian landscape is deluged by rain, and the skies remain overcast.

Uderzo continued on his own for many years with rapidly diminishing returns. His first three solo efforts aren’t bad (Great Divide, Black Gold, Asterix and Son) but they swiftly begin to rely too heavily on anachronisms which had hitherto been more subtle; returning characters; and on elements of the fantastic (magic carpets, Atlantis). A new team of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad took over when Uderzo retired (he died in 2020, aged 92) with mixed results. Asterix and the Picts was not a strong start – Nessie owes too much to Uderzo’s more fantasy-oriented Asterix – but Chariot Race is arguably the best album since Belgium. The new writer & artist, Fabcaro’s next book – Asterix in Lusitania [Portugal, more or less] – is due out this month.

In the early 2000s Orion books in the U.K. finally invested in Asterix, standardising the design and layout, using the newly-recoloured artwork (this website covers the restoration: https://asterixthegaul.com/2025/06/the-great-restoration/), and finally bringing the British edition’s numbering in line with the original French chronology. This means that Asterix and the Banquet (for example) is the 5th volume rather than the 23rd. Readers in the U.K. may previously have been bemused by the introduction of a little dog who tags along, unnoticed, behind Asterix and Obelix on their Tour de Gaul, when it’s clearly Dogmatix, who the reader first encountered in what was ostensibly the 2nd volume, Asterix in Spain. Now it made sense!

The remasters are largely superb, and about half of my/my son’s collection is now in the uniform white cover design. They’re the comic equivalent of lossless streaming, but sometimes you want a scratchy old 7”, and that’s why I also love the old editions.

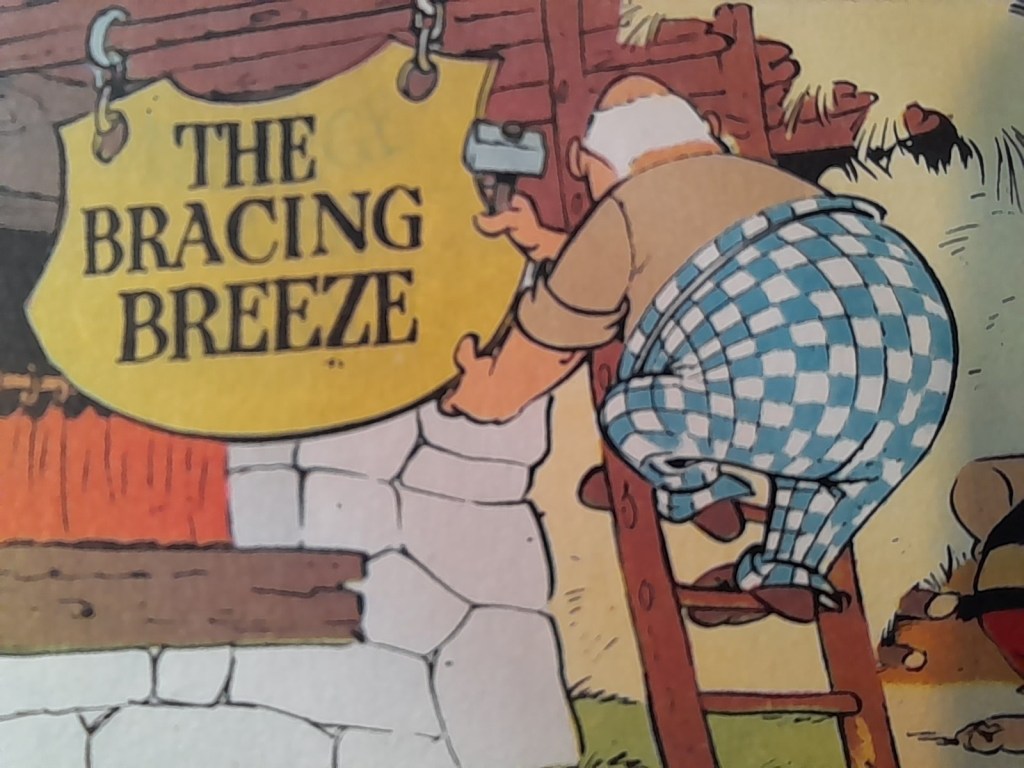

Even the weird colouring anomalies or misaligned printing have a certain charm. Sometimes you can just see the ghost of the original French underneath the sound effects, or as on this inn sign in Caesar’s Gift, where you can just see the word “auberge” (from “auberge de la brise vivifiante”).

It’s now 30 years since the publication of the only full-length study of the Asterix books in English, Peter Kessler’s excellent The Complete Guide to Asterix. Since then, sites like Gareth Thomas’s mothballed Alea Jacta Est or asterixthegaul.com have provided in-depth resources for English-language fans of the series wanting to dive deeper into the many layers of Asterix.

Notes

1 I have an April 1961 copy of Pilote, as it happens – I bought it on ebay because there was a feature on Belgian cyclist Rik van Looy – but sadly there’s no Asterix: Goscinny and Uderzo (not to mention the oft-uncedited inker Marcel Uderzo), were working on Asterix and the Goths. What my copy does have instead is the duo’s Jehan Soupolet in “le corsaire du roy” (also known as Jehan Pistolet) about a freckle-faced adventurous young lad who becomes a privateer.

2 Brockhampton later became an imprint of Hodder and Stoughton, whose name was on the spine until the 21st century remasters when it was replaced in turn by Orion: all of these imprints are now part of the Hachette group.

3 Goscinny named him Anglaigus (acute angle).

All images obviously (C) Les Éditions Albert René/Hachette

One thought on “Asterix!”