Something a bit different. I go for cycles more than I do walks, and the back roads of East- and Midlothian are my usual haunts. I’ve explored some of the old coal mining region in a previous post. A ride on a road bike is necessarily restricted to roads, because you can’t branch off onto paths and other interesting routes unless you like repairing punctures.

But a ride at 25kph reveals more of the world than a drive at 100kph. Over time, as well as getting to know each little climb, corner and descent, curiosity about the countryside I travel through has prompted me to learn a little about what’s a superficially uninteresting corner of Scotland. Certainly there are neither lochs nor mountains, but the moors and valleys of Midlothian reveal much about the past, and speak of a busier rural history than today’s concentration of ex-mining villages would suggest. Additionally, a keek at the origins of place-names (and this obviously works anywhere) also gives us a glimpse into the past.

Get your bike out and join me.

***

Dalkeith lies around 10 kilometres south-east of Edinburgh. At its western point the rivers North and South Esk [Esk from Gaelic ‘uisge’ meaning water, as in ‘uisge-beatha’ = ‘water of life’ = whisky] meet, and flow out to the Firth of Forth at Musselburgh. Although there are few signs today of heavy industry, the first recorded instance of coal mining in Scotland was at nearby Newbattle Abbey, and in the Middle Ages it supported a huge salt industry on the shores of Forth. For much of its life Dalkeith has been a typical Scottish market burgh, though the large number of coal mines in the area gave it a different profile from other such towns. Villages like Danderhall, Newtongrange and Loanhead were more reliant on coal-mining but Dalkeith, as the largest town in the area, found itself a hub during the bitter miners’ strike of 1984-85.

Our journey begins in earnest at Hardengreen roundabout on the A7, where the road is crossed by a new bridge which carries the re-opened Borders Railway. The road narrows and twists before it crosses the South Esk, and this is always a nervy moment for the cyclist. On your left, next to the river, is the Sun Inn.

This, somewhat implausibly, is one of two such pubs that bore the name within a kilometre of each other. The other, across from the entrance to Newbattle Abbey College, is now a private residence. The sun is the heraldic symbol of the Earls of Lothian: it also appears on the Midlothian coat of arms, and on some statues atop a wall near my house.

What catches the eye here, of course, is Lothianbridge viaduct which carries trains across the South Esk valley.

After the Sun Inn, the road climbs towards Newtongrange, and the cyclist finds themselves in a dilemma. The road splits: straight ahead will take you to the bottom end of Newtongrange (“Nitten”) and up towards Bryans, Easthouses & Mayfield. Taking the right-hand fork keeps you heading south on the A7. Traffic coming from behind is fast, and the trick is to time your signal and move out at the right time. Too early and you hold everyone up; too late and you can’t get across. All the while the road is climbing; it’s a little extra stress you could do without.

On your left is a thickly-wooded hill whose verdancy disguises its true origins: this is “the bing”; a spoil-heap, by-product of the local coal mine. Staying on the A7 and passing under the viaduct, on your left are houses which occupy what used to be Victoria Park (and indeed the housing estate bears the name), home of Newtongrange Star F.C., one of several local junior (meaning non-league, not “for kids”) football teams that the mining villages gave rise to. The football club now have a tidy, modern ground built atop the bing.

You’re currently by-passing Nitten. As the wonderfully named Murderdean Road rises and crests a bridge over the railway line, you reach a junction where you can turn left into the village. I used to live here: a planned village, built almost entirely to service the local mine, the grid-like layout of streets are all numbered: First Street, Second Street, etc. Near the bottom of Main Street is the Dean Tavern, a pub run on “Gothenburg” principles. These were pubs whose aim was to raise funds for local improvements (parks, welfare clubs, etc), ploughing the profits back into the local community rather than lining the pockets of distant shareholders. The interior was minimal, even austere: the pub was not supposed to be welcoming, or to encourage excessive drinking.

Anyway, back on the A7. During the general strike of 1926 armed soldiers were stationed on Murderdean Road with orders to shoot, in the event that there was any form of uprising from the miners. How aptly-named the road may have proved. The coal-mine in question, the Lady Victoria (“The Lady”) closed in 1981 and is kept in superb condition as the Scottish Mining Museum. The winding gear is a local landmark, visible for miles around. It’s definitely worth a visit, and has an extensive research collection, housed in the former colliery offices on the other side of the road.

We’ll take a left now, off the A7, and here the road climbs sharply past the Stobhill recycling centre, towards Gowkshill. Gowk means ‘cuckoo’ in Scots but I’ve never heard, far less seen, a cuckoo here.

There are bright new houses on the left as you climb: this is the site of another abandoned coal mine, the Lingerwood pit. If you buy a house around here you need a coal report done: what’s underneath? It must be like a honeycomb. A black, flooded honeycomb.

The road continues to steepen; at the top is the site of an old Roman Camp, and was the residence in the early nineteenth century of a local witch, known locally as “Camp Meg”.

Onwards, past the sawmill, to left is Gallows Hill; there’s also a Gallowknowe on the eastern flank of Newtongrange. How much hanging went on in these parts? I don’t know that, but I do know that the Lothians had a depressingly large number of witch-hunts.

In a 16-month period from 1661-1662 there were 206 people in East- and Midlothian named as witches (four times the numer at Salem), and at least half of those were burned alive as punishment. Whatever their perceived transgressions, there’s a good likelihood that if these poor souls had gathered plants and herbs for the herbal remedies they made, then the descendants of those plants (or even actual trees) are in the fields and roadside verges we pass.

At the very top, ignoring the road east towards Vogrie country park, the road summits and affords a stunning view of Midlothian: from Moorfoot hills to Pentlands, with the Esks in between. Take a breath here, if you want: you’ve earned it.

The road surface is shocking, which makes an otherwise pleasant freewheeling descent a more stressful ride than it should be. Where it levels out, just past a crossroads, is one of only a handful of standing stones in Midlothian: Wrights Houses, named for the nearby cottages (which it presumably pre-dates by centuries, if not millenia).

Is it a way marker, a boundary post, or sacred relic? Alfred Watkins, who introduced the idea of ley lines in his book The Old Straight Track, specified a ley as a line of sight which linked at least five sacred or otherwise notable structures in a row. Nothing to do (necessarily) with earth energy, UFOs or anything else; he simply and reasonably assumed that early man would have chosen the most direct pathways between sites of importance. Wrights Houses, according to the internet, is not on a ley, nor have I been able to establish any significant lines of sight or alignments. Any information would be welcomed.

We descend quickly, snaking over the railway and into Borthwick and past the fine, austere cuboid of Borthwick Castle. J.C. Carrick, in his Around Dalkeith and Camp Meg, describes this particular glen, between 11-12 at night from June to August, as being filled with glow-worms: I wonder if this is still the case; I’ve only ever seen them in France. [January 2020 update: my son, who has camped in this area several times with Scouts, tells me he has seen them. I should’ve asked him sooner…]

Onto a short, steep climb the road narrows, and trees overhang. It reminds me slightly of a Belgian hill used in the toughest professional bike races there – the Koppenberg – though this nowhere near as long or as steep, and it isn’t cobbled. It does let me indulge in a brief fantasy of cycling glory as I haul my sorry arse up it, though. After the top is a gruelling false flat to the village of North Middleton, across the A7 from which is a lime works. This continues a historic industry: a few miles away, beyond Gladhouse reservoir, are the remains of historic lime kilns. There was once a huge lime industry in Midlothian: we’ll pass some old quarries in a little while. The lime was used for agriculture or construction and not – ironically, given the number of such mills on the Esk – in paper production.

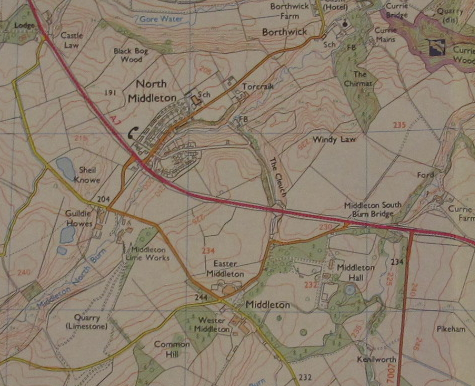

We’re back on the A7 here. There are a few weird road orientations to either side on the stretch between North Middleton and the turn-off for Innerleithen, which only made sense when I studied a 1950s map of the area. At Middleton South Bank Bridge a slip road off to the left runs to a farm, and this is actually the route of old A7, which used to follow the contours of the land more closely.

Cut ends of a route that used to be sympathetic to the contours of the land.

The direction of a few other roads whose orientation seems arbitrary makes sense when we see the ghost of the old trunk road.

Above, the A7 (red) in the 50s. Below, the same stretch of road now.

Swing right onto the A7007, known locally (because of the quarry at the top) as “The Granites”. I love this road, and have ridden it in all weathers. There have been days where an (abnormal) easterly wind has been so strong I’ve ridden up the hill faster than I then descended it. I’ve seen short-eared owls here, numerous curlew (though fewer and fewer in recent years), lapwing (ditto), and even the roadkill corpse of a black grouse.

Today we’ll ride to the top and simply turn around. The road beyond is well worth taking (you cross the line dividing Midlothian from the Scottish Borders just shy of the summit), but we’re staying between Moorfoot and Pentland today.

The first time I rode up here I knew nothing about it: the name of the climb, even the name of the hills, only that the road had been freshly resurfaced and was wonderfully smooth. Now, well over a decade later, a combination of traffic, the run-off of water from the hills and the effects of winter ice have all cracked the tarmac in many places, but it’s still an enjoyable ride, one where every corner promises to reveal the summit but in the end reneges. The top is always a few gently sinuous curves from where you think it’ll be.

The descent, naturally, is also great fun. I think I’ve reached 72km/h with a favourable tailwind. It isn’t steep, but it’s long and fairly straight. Instead of returning to the A7 we’re taking the left turn to Middleton (distinct from North Middleton – keep up) and a further left to climb the shoulder of Esperston Law [Esperston = Eastbeorht’s Farm]. The photo below doesn’t quite capture the feel of this hillside: at the top, and – significantly – unreachable from the road, the crown of the hill is devoid of vegetation. I always think of it as a “blasted heath”, with echoes of both King Lear and ‘The Colour Out of Space’:

This area is full of abandoned quarries, precursors of the lime works. It’s a thumping great cliche that the landscape is a palimpsest, but only a cliche because it’s true. Here, man-made lumps and bumps in the ground, all softened by time, signify the sunken ribs of past industry. Some of these are too unnatural to go unnoticed:

Further on, taking a turn towards the excellently-named village of Temple, we come across the mysterious conveyor. Notable enough to feature on maps, it connects the lime works with a distant quarry. I’ve never seen it in action.

Some place names seem to need little explanation: there’s a farm called Outerston, at the very fringe of inhabited Midlothian. Yet to assume that it meant “outer” would be wrong. After all, in an age when individual settlements were less-well connected than today (or, at least, the travelling between them took more effort) the naming of places was much more cellular. Outerston was not at the periphery of a notional “centre”, in the way that, relative to Penicuik or Dalkeith, it is nowadays. Names were bestowed on a local level, and because they were generally descriptive, that’s why so many place-names (worldwide) are, at root, similar.

That is, they reference distinctive geographical features which at the time would have signified a unique spot to the people of the locality in question, but which may be a common feature in landscapes generally. There would be no need to specify which wood or river or hill a placename derived from because either there was only one in that area, or else the placename itself made the distinction.

So although over time the names may have mutated, a huge number of place names (from farms all the way up to capital cities) are, etymologically, very simple descriptions. In this case Outerston means Utred’s or Uhtric’s farm

And then you get something like this:

Some names, by contrast, pull you up short by their very strangeness. Either the name itself may be unusual or a familiar word is used unexpectedly, as is the case with Temple. The village – or more specifically, the Old Kirk (below) – was the Scottish HQ of the Knights Templar from the 12th Century. A strip of a village built entirely on a hill, it’s a satisfying climb but less satisfying descent because of all the speed-bumps.

Rattling down a road whose surface the years of water dripping from overhanging trees has rutted, we briefly join the road to Penicuik [pen-y-cog = hill of the cuckoo], cross the Braidwood bridge [‘broad wood’, and the woods here in the grounds of Arniston House are thick as they line the South Esk] and head towards Carrington. Carrington – a huddle of cottages around a junction – has a curiously English feel to it, I always think: the sort of place you’d see in some B&W 50s film and indeed one afternoon recently, near to this spot a 50s car (Rover? Morris? I’ve no idea) passed me. For a moment you might be tempted to think “timeless image – could be the 50s” but this is a fallacious, if seductive, line of thought. After the car had passed, I cycled by a strip of leylandii, which gave the lie to the myth of an unchanging rurality.

Although merely the most recent re-enacting of a ritual as old as settlements themselves, yesterday’s ploughed field is – technically – a more recent act than last year’s steel and glass office block. The chemicals in the field are modern; the consequently reduced biomass is modern; the changing fortunes of other species (nuthatch are a recent arrival in these parts; goldfinch numbers are booming) are modern. There are houses – renovated, occupied – older than the ruined limekilns.

We leave Carrington and head for the crossroads at Cockpen [cuckoo hill – spotting a theme?]. April 1st was, as well as April Fools Day, also the local day of “huntigowk”, and “gowk” means not only “cuckoo” in Scots but also “a fool”. Near Penicuik there’s a “gowk stane” (which I’ve yet to visit) that has it’s own lore.

On the way to Cockpen we pass a farm whose name is guaranteed to trigger an earworm of Billy Ray Cyrus’s early 90s country-pop monstrosity, “Achy Breaky Heart”:

An interesting thing about the subjectivity of a bike ride is that depending on the direction of travel, the same stretch of road can hold two very different meanings or sets of significance in your head. There are roads which, if taken early in the day can trigger memories of feeling particularly fit; yet if taken at the end of a ride on the way home may seem endless as your weakened legs struggle to turn the pedals.

It’s easier to have a 360degree experience of a spot if you’re on foot: you can turn around easily. It’s harder to do on a bike, so what you see when you’re heading south may differ entirely from what you see heading north at the same place, and you may never put the two views together in your mind. There may be stretches where we know each pothole or puddle, on either side of the road, but may never twig that it’s the same place.

I mentioned birds earlier: the stretch from Carrington to Cockpen is great in the summer for yellowhammers. Their “little bit of bread and no cheese” carries some distance, and their habit of perching atop hedges makes them easy to spot.

Up the hill by Cockpen church we skirt Bonnyrigg along what I always think sounds vaguely futuristic – “Bonnyrigg Distributor Road”. This is a modern route designed to serve the newbuild estates that fringe Bonnyrigg, and act as a bypass for traffic coming from the south.

Dalhousie is a place-name unavoidable around here. There’s no agreed etymology for it, though “valley of wool” and “field/meadow of the wood” (the same derivation as Dalkeith) have both been suggested. Whatever the origin, there is a Castle, a Burn, a Mains, a Grange, an Upper-, a Strip Wood, a Chesters [signifying a Roman camp] all named for it, and at least two of the local schools have houses called Dalhousie.

Many place names which no longer refer to geographical features have instead some connection with powerful families. These give us an insight to the pattern of ownership and domination wielded by the elite over the centuries: names like Borthwick and Ancrum/Ancram speak of patronage and titles and inheritance available only to those whose ancestors were favoured by royalty.

As we come back to the ring of old mining villages, the creep of middle-class housing, glaring white in the sun, is everywhere. The villages grow closer together all the time with that weird triumphal habit of naming new housing developments for whatever their construction has bulldozed: another palimpsest. “Oh, there used to be a meadow here. Now there’s some bungalows with Range Rovers.” But however much we change the face of the landscape, the names still tell a story.

Sources

Dixon, Norman – The Place-Names of Midlothian (University of Edinburgh, 1947)

Carrick, J.C. – Around Dalkeith and Camp Meg (P&D Lyle, 1912)

Spokes – Midlothian Cycle Map

OS Explorer 345 (Lammermuir Hills)

2 thoughts on “Esk Valley & Moorfoots: a ride”