I wrote here (and more pertinently here) about maps in fantasy books, and for no justifiable reason I want to look at the ways in which the nature of Clive Barker’s work is largely resistant to cartography.

When we think of fantasy maps we tend to think of Christopher Tolkien’s classic Middle Earth one (although I always liked the one in The Return of the King with all the contour lines), or the various maps of Westeros in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. You all know what I mean. Barker, though, said in 2022 that “I have no desire whatsoever to create a Middle Earth. None. I have a desire to create fifty Middle Earths, and draw the roads between them – and that’s a very different thing. I think that fantastic worlds can be smothering to the creative impulse.”1

To any reader of his fiction, this is self-evident. Barker almost never revisits a world that he has created. The exceptions – which I’ll look at first – are the children’s series Abarat and the dream sea Quiddity in The Great and Secret Show and Everville: and in each case – albeit in different ways – the world he describes on the return is not the same as it was the first time. To map a thing is to say that it is fixed, and Barker constantly resists such ossification.

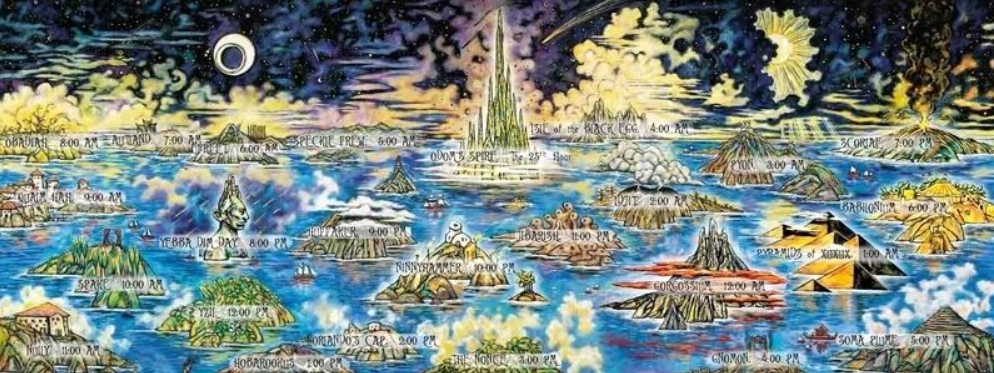

In Abarat he built into the very structure of the world an escape hatch from any sense of smothering: there are twenty-five islands in the world of the Abarat, each separated by the Sea of Isabella, and each island is an hour – that is, on one island it may perpetually be three in the morning, and at a neighbouring one, eternally five in the afternoon, and so on. Now, without checking, I don’t think that in the published books every island has been visited, which means there’s still room for creative manouevre in the remaining volume(s), bound only by the hour of the particular island, and the description of it found in the fictional ‘Klepp’s Almenak’ in the first volume of the series. The closest we get to a map in all of Barker’s work is the lush panorama of the Abarat, midway through the first book, but the islands are not to scale, and show only the “famous” buildings or features: shorthand, in the way a map of France might show the Eiffel tower, or New York be represented by the Statue of Liberty.

Barker’s imagination is ceaseless, his imaginings protean and although this can sometimes work against him, I’d far rather have an over-imagined fantasy than an under-imagined one: better bloated than starved. It can also lead to a certain inconsistency: Everville being a case in point. In The First Book of the Art, The Great and Secret Show, the protagonists are plunged into the dream sea of Quiddity which humans normally only visit on a maximum of three occasions: the first time they sleep after being born, the first time they sleep with the love of their life, and the last time they sleep before death. What the characters discover is that the sea works itself upon the bodies of those who visit its waters in the flesh: they are transformed by coral-like encrustations, (“the waters take human flesh and fantasticate it”, as Ruty says in the related story On Amen’s Shore2) and the more one tries to resist the effects, the harder the sea works. When we revisit Quiddity in Everville, none of this holds true. In the interening years, Barker has opted to expand upon his original vision of Quiddity – fair enough, it’s what we want him to do – but at the price of the place visited being consistent. With Barker we never step into the same ocean twice.

***

And what of his other worlds, those he has chosen to visit only once? For many of those books set in “our” world, the topography is of secondary importance. Cabal is set in Canada, and the Nightbreed’s refuge of Midian is the deliberately vague “east of Peace River, near Shere Neck, north of Dwyer”. Peace River exists but beyond that the necropolis is in the imagined wilds of Alberta. A map of Midian is unnecessary: its significane lies in its very existence (although for the film adaptation, Nightbreed, it obviously needed planned out).

Most of his work is primary world fantasy, in which a secondary world (or elements of it) irrupt into this one. The most obvious example of this is Weaveworld, in which a carpet contains an entire world – the Fugue – that’s home to the Seerkind, and the last vestiges of magic available to this world.

The Fugue resists any attempt at cartography. Part of this is the arbitrary nature of its features: “a random assembly of spots the Seerkind had loved enough to snatch from destruction” when they were being hunted by their mortal enemy, The Scourge. Part of it is the equally arbitrary unspooling of the world when the carpet is undone – first, on the real-life Thurstaston Common, and later in an anonymous glen in the Highlands.

When our hero, Cal Mooney, first sees the carpet, he’s balancing precariously on a wall while trying to recapture one of his father’s racing pigeons3, and the carpet is being moved from the house of its erstwhile guardian, Mimi Laschenski. He has a brief, tantalising vision of the Fugue, where a “casual indifference to organisation was evident everywhere, he saw. Zones temperate and intemperate, fruitful and barren were thrown together in defiance of all laws geographical or climatic, as if by a God whose taste was for contradiction”: or an author, one might add. He also glimpses “a lake…a dappled quilt of fields…velvet woodland…[and] a town too, laid out in a city-planner’s nightmare, half its streets hopelessly serpentine, the other half cul-de-sacs.”

The geographical features of the Fugue (Venus Mountain, the orchard of Lemuel Lo) are significant, but their position and proximity to one another is not – other than to circumvent the need for lengthy fantasy-style quest journeys. Only the Loom, the metaphorical and literal heart of the Fugue, is in a fixed place – the centre – and presumably from the Loom, the haphazard position of everything else is spun out: “there appeared to be no system to the geography.” Elsewhere, “curious juxtapositions abounded. Here, a bridge, parted from the chasm it had crossed, sat in a field, spanning poppies.” For all the wonderful description, as with the far briefer and more impressionistic Cabal, Barker is sketching with a lightness of touch which leaves enough to the reader’s imagination: and that’s one of the keys to his work. Although a very visual author, enough room is left for us to fill in the blanks (or not) when faced with a description of a place or creature whose features are only partly described. We don’t need every forest or tentacle accounted for.

In the 1991 novel Imajica, the absence of an authoritative map is a lack which that book’s troubled hero, Gentle, intends to fix. But, crucially, we are not given one ourselves with which to orient our journey across the Five Dominions (of which our world is the Fifth, sundered from the others). It’s the only other of his novels with a detailed secondary world (four of them!).

Once Gentle’s task – of reconciling Earth to the other four Dominions – is complete (spoiler alert!), he and his lover Pie’oh’Pah set off across the hitherto obscured First Dominion with the aim of mapping it4. In a way, it’s an odd thing to do. Understandable – nobody but he has ever ventured into the First and survived: for generations it was populated solely by the vengeful masculine diety Hapexamendios. But Hapexamendios forced his phallocentric, singular and quite fascistic vision onto the world and while I’m not equating cartography with fascism, setting things down on a map does imply a single point of view and acts to undermine any fluidity or ambiguity within a landscape.

But Gentle’s mission is a benevolent one. Before leaving the Fifth, he made sure that its inhabitants (i.e. us) could find their way into and around the greater existence they are part of but, until the Reconciliation, never knew. As his artist friend Monday exclaims, “he wants us to draw this map on every fuckin’ wall we can find!” and this map, of course, is as much symbolic as topographic.

As with any cartographer, Gentle runs up against the eternal problem: “maps were always a work in progress.” Upon arriving in the transformed city of Yzordderex, Monday – who has only heard about the place – cries “where’s the palace? Where’s the streets? All I can see is trees and rainbows.”

The latter pages of Imajica appear to show Barker’s own feelings on the place of fantasy maps: that they should be within the fiction, on the same ontological level as the characters, and thus invisible to us readers: “maps were cursed by the notion of a definitive original. They grew in the copying, as their inaccuracies were corrected, their empty spaces filled, their legends redevised…they could still never be cursed with the word finished, because their subject continued to change.” So what would be the point of including a map in the book?

Notes

1 https://www.clivebarker.info/intsrevel37.html

2 Available here

3 A Weaveworld map of Liverpool, showing where Cal and Suzanna’s adventures take place (allowing for the fact that Cal’s home of Chariot Street is fictional), would be welcome. There are several equivalents online for Stephen King’s Derry (based on his home town of Bangor) from IT.

4 “He still had the map of the desert between the gate of Yzordderex and the Erasure to set down, and though these pages would doubtless be the barest in the album, they had to be drawn all the more carefully for that fact: he wanted their very spareness to have a beauty of its own.” This fascination with deserts stems from Barker’s childhood love of the books of explorer Wilfred Thesiger, and can be seen, too, in one of Weaveworld‘s most haunting passages: the voyage of Shadwell and Hobart into the Rub Al Khali, where they encounter Uriel in the ruins of what may have been Eden.

One thought on “The Unmappability of Clive Barker”